Wind of Change

How to manage organizational change, while trying not to quote 90s hard rock

A Failed Change

The program was about to start, or we thought it was. Many years ago, we had just signed the biggest deal in the company’s history and pressure was growing to start work.

I pulled my leaders into a room, and led a number of very productive sessions with them detailing how we would shift our staffing and people’s assignments to both serve these new projects and continue to make progress with our existing work.

The changes were communicated to the relevant teams and set into motion.

I missed the fact that zero dependencies were ready and none of the new team members could do any meaningful work. Money was wasted, and the top-down direction to start despite this lack of context or dependencies led to false starts everywhere. People made assumptions and diligently began any work that they could - and then immediately became extremely frustrated.

Ultimately, employee engagement took a massive hit and it took months to recover.

The broader change was the right one and very necessary, but what did I do wrong?

I would have noticed from speaking to folks closely connected to the work that those dependencies weren't ready. From there and with that context, that time could have been spent listening, altering the plan, and engaging the right people to craft the right message and objectives that could have been repeated and understood by everyone.

Change is Hard

Change is really hard.

No matter how good your reorganization plan is, no matter how “no-brainer” your strategy is, it will fall flat if you forget the people involved. Planning how the message gets delivered and who receives it is not something that happens at the end - it is an integral part of the planning process.

There are countless books on change management that may state these concepts more elegantly, but these are my main considerations honed over the years, learned mostly the hard way.

Do Not Surprise with Decrees

As a leader, it is not your job to deliver blinding flashes of brilliance by surprise. Surprise excludes the crucial input you need for your plan from all of the smart people on the ground.

Ideas presented like stone tablets are non-negotiable, non-changeable orders. There are some organizations that may appear to operate well under this model, but the broader perspective is that most of us don’t feel compelled to follow orders “just because”.

The ideas are out there in your team right now. The process of delivering the message starts with asking and listening to folks in your organization. What’s working? What’s not working? What do they see?

Never under-estimate the power later of people hearing the same message or theme later in the strategy. They’re now part of it!

As the strategy, vision or re-org starts to develop, keep the conversations going. The mode switches from information gathering to planting seeds of context. Who are the key influencers in your organization? Who will help explain the ideas to others when you as the leader can’t? Those people need to be consulted. Tweak the message based on their feedback.

The more people in the organization that feel that it is OUR idea, not YOUR idea, the more resilient the message will be and the greater impact of the change.

People are not going to do things just because you tell them to. They will engage profoundly with ideas that they felt that they had a part in shaping.

Perspectives of Concern

The first time any of us consider a change, our brain goes to the same place, asking the same questions.

• How does this change affect me?

• What happens to the people around me on my team?

• What does this mean for my organization and company?

Any message around a change has to address each of these questions.

The main problem I’ve seen over the years with leaders explaining a change is that they only cover one of those perspectives, usually the organizational one.

What this fails to do is connect that perspective to the actual people in the organization, and since it remains abstract, no individual can personally and intuitively relate to it.

Remember these perspectives of concern, and speak to all of them

The Cycle of Grief

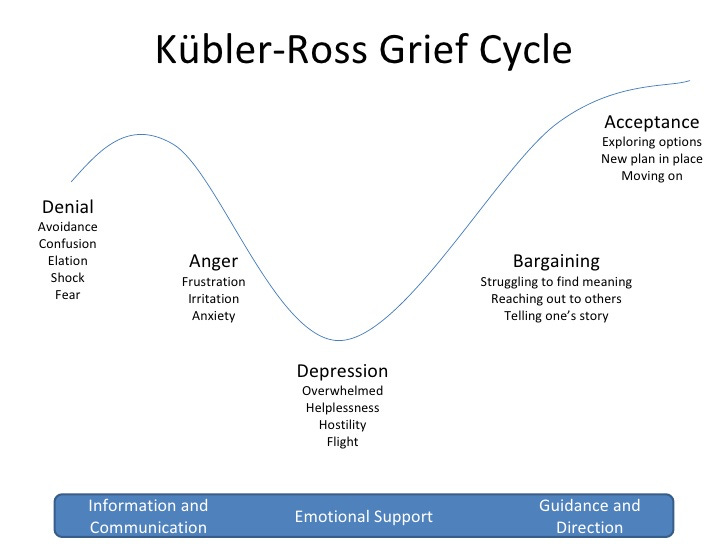

The Kubler-Ross cycle, used when describing grief and how we process and adapt to it, consists of five stages:

1. Denial

2. Anger

3. Bargaining

4. Depression

5. Acceptance

These are better expressed in a diagram, where each stage is laid out horizontally, and the line represents wellbeing and sentiment, higher being better and healthier.

Now, accepting change in a professional context does not begin to reach the levels of emotional upheaval experienced in grief, but how we process fundamental changes is always consistent.

Adapting to change takes time and patience on the part of the leader to allow acceptance of the change. What is needed from you as a leader is to communicate, support and guide.

People may appear in a limited perspective to be angry or upset with the change. This could be someone struggling to adapt to the change, but remember that this reaction exists within a broader model. This isn’t their final answer, but a step on a journey that they need your ongoing support for.

The Rule of 7

The best thing a leader can do in trying to communicate and reinforce a change is to be consistent and repeat the message, over and over, in different forums.

There is a marketing principle called the “Rule of 7”, that states that people hearing a message need to hear it at least seven times before taking action. This principle applies to internal corporate communications too.

This is starting to work when you hear other leaders or individuals repeating the core ideas in the changed strategy, but using their own words. This means that the message has landed, and they are starting to synthesize their own independent perspective on it that is still consistent with the broader concept.

Embrace Change

Don’t be afraid of change. Consider the broader human element and put in the effort to properly communicate and prepare, and watch the outcomes improve.